Fuckboy Fuckboi Fuccboi

“Welcome to the generation of fuckboys,” envisioned a Thought Catalog article, as it invited readers into discussion of this “new species” of 21st century man. Putting aside the unlikely event of a homo fuckboy discovery, this text offers valuable depictions of how heterosexual dating culture is addressed in present-day media and, more broadly, points to the current state of gender politics in Western (particularly Anglo-American) society.

In most analyses, “fuckboy” (alternatively spelled fuckboi or fuccboi) has been described as an irresponsible, misogynistic, and sex-obsessed younger man, and the term may be the first sexualized insult for men (akin to “slut” or “whore” for women). However, it is difficult to pin down an exact definition of the word, especially because of the vastness of the discourse. Interestingly, though, the Fuckboy is presented an inescapable, natural, and even somehow desirable fellow in dating life: “This type of guy clearly has an allure since so many women continually fall for him.”

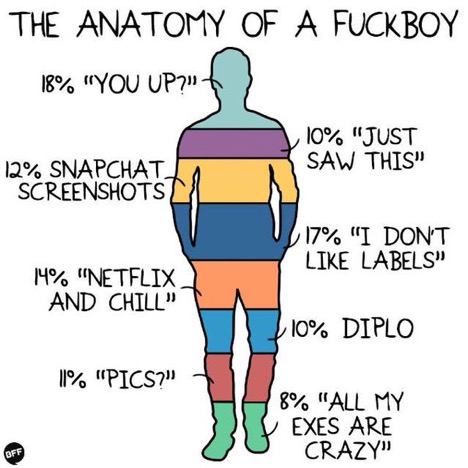

Exposés on this young adult masculinity offer identifying characteristics of the Fuckboy (see Figure 3), appropriate responses to Fuckboy behavior, and the lexical evolution of the term. In particular, Fuckboy media either speak to women about how to identify and manage Fuckboys or instruct men on how to avoid acting like a Fuckboy. Regardless, the newly minted slur for young men seems only to be growing in popularity and mystique.

Figure 3: Anatomy of a fuckboy with social media and popular culture references. Note: Reprinted from Your official fuckboi field guide: How to identify them in the wild.

This chapter presents the evolution of the term “Fuckboy” by situating the Fuckboy discourse’s masculine/feminine interactions in past relationship advice media contexts and recent discussions of how digitalization has affected mediated intimacy. My aim in this pursuit is to determine why the Fuckboy is a derided character yet inevitable and still somehow attractive. I also address the aspects of digital and social media in the Fuckboy with the hope of unraveling the discourse and elucidating how real-life experiences have been translated into the mediated Fuckboy. The case of the Fuckboy explains how increased visibilities of feminism and misogyny and the age of digital media dominance have manifested in mediated sex and love advice.

History

Sex advice for men

As mentioned in the previous chapter, I view mediated (postfeminist) masculinity as a comprehensive sensibility. I approach the Fuckboy discourse as a part of this sensibility. Since the vast majority of Fuckboy media offer advice to either women or men on how to avoid or avoiding being a Fuckboy, respectively, I use narratives of sex and dating from within media of the last 10 years to illustrate the Fuckboy’s characterization.

In lifestyle magazines aimed toward men, particularly 1990s Lad mags, young men have been told to view sex as their persistent goal and a natural expression of manliness (Gill, 2009b). Gill (2007b) has expressed that these magazines showed masculinity “in terms of playfulness, flight from responsibility, detached and uninhibited pleasure-seeking, and the consumption of women’s bodies” (p. 217). The New Lad discourse can be viewed as a comprehensive arena of media, including books and films known as “Lad lit” and “Lad flicks,” respectively, that was aimed toward these young men in the 1990s and 2000s (Gill, 2009b; Hansen-Miller & Gill, 2011); Lad culture was also criticized for its role in the normalization of female sexual objectification and sexual harassment, particularly on college campuses (Gill, 2014).

In a discussion of the emergence of these lad flicks, Negra has hypothesized that the already much-visible “deficient/dysfunctional single femininity” of the early 2000s had begun to be “matched by deficient/dysfunctional single masculinity in a number of high-profile films and television series” (2006, n.p.); this problematized image of manhood has been deemed the “player” type by Hansen-Miller and Gill (2011). This depiction maintains the white, heterosexual, and fallible masculinity of the hedonistic New Lad, but with a more pronounced focus on his renouncement of love and monogamy (Hansen-Miller & Gill, 2011). Within these film and book narratives, the player is often spurred to mature and accept responsibility for himself and his life, a transformation that is often provoked by a woman in his life who is responsible, mature, and ready for long-term monogamous intimacy.

The player lifestyle is caused by immaturity and some childhood trauma, and in the end, the labor of a successful woman is the cure to male promiscuity. The genre is characterized by “the gleeful celebration of laddish pursuits,” in such a way that these films’ comedic value is embodied by “the juvenile nature of culturally identifiable masculine values and ideals” (Hansen-Miller & Gill, 2011, n.p.). In other words, men’s misbehavior is the crux of hilarity.

The focus in lad lit and lad flicks on gratuitous sex, particularly when it involves manipulation or strategy, exhibits men as naturally predatory to women, and while the characters apologize for this behavior, it is excused as honesty and an authentic representation of what all men do (Gill, 2014). This characterization has the effect of normalizing misogyny in its modeling of heterosexual relationships. Gill (2014) has argued that these postfeminist media depictions of romance are the most comprehensive and widespread in the Western world. However, dating culture has since adapted to the technological and sociological transformations from digitalization.

Sex advice for women

Rosalind Gill’s (2009a) discourse analysis of sex and relationship advice in women’s magazines uncovered many contradictory sentiments regarding expectations of women and men in heterosexual dating. While these media are targeted to women, their configuration of manhood through the female perspective is inherently part of the masculine sensibility; just as men and women do not exist on different planets, gendered media are influenced by outside sources. Consequently, as the fuckboy discourse occupies media that speak to both men and women and have been created by both men and women, it is important to view the history of both sides.

In the women’s magazines, there was a strong focus on sex, which is not surprising when viewed from a postfeminist lens, though homosexual relations were markedly absent. The discussions of heterosexual sex in the magazine indeed encouraged women to actively explore their sexual subjectivities and the self, insofar as the sexually subjective self was one “closely resembling the heterosexual male fantasy found in pornography” (Gill, 2007a, p. 152). Gill (2009a) surmised that young women in Western society should have vast knowledge of and experience with sexual behavior, matched only by the limitless sexual desire of men shown in media.

At the same time, these magazines suggested that women’s primary goal is to seek committed romantic relationships, and to find their ideal boyfriend, they must determine the precise characteristics they want in a man. Finding someone with each of these qualities is meant to be attainable if the women put in enough time, thought, and work. Importantly, the magazines encouraged women to constantly work on the self, and the perfect way to do so is to practice relationship techniques by interacting with potential partners who are deemed unsuitable (Gill, 2009a, p. 354).

The advice in the magazine proposed that women must be the managers of their emotional relationships, such that they be calculated and always attentive in their interactions with male partners to psychologically manipulate men into being romantically or sexually interested in them. Gill (2009a) said of the advice, “Men’s needs must be recognized, perhaps even anticipated and pre-empted, by women, while women must silence their needs if they wish to win male approval” (p. 365), which represents a markedly disproportionate delegation of power and work in heterosexual relationships. Throughout the magazines, men were presented as “benign and lovable,” yet entirely focused on seeking sex (Gill, 2009a, p. 363), but this libidinous presentation is suggested to be just the nature of men, such as in the retrosexual or New Lad discourses. Furthermore, it can be speculated that lad flicks’ problematizing of young, white, male, heterosexual promiscuity progressed this discourse to the online world, from which emerged the Fuckboy.

Online dating changed everything…or did it?

Online dating websites and, more recently, mobile dating apps have proliferated, thus increasing the available spaces for constructing contemporary heterosexual relations. The online nature of these interactions means that there is the potential to have documented evidence of how dating is approached, which is an essential part of the Fuckboy discourse. The most popular dating-centric space among young adults is the mobile app Tinder. Tinder is mostly based on location, so potential matches are typically within a certain radius from one another. The app is based on users swiping right or left on profiles to indicate if they find the person attractive or not. If two users swipe right for each other, then they match, which opens the possibility to exchange text messages through the app. Due to its proximal characteristic, Tinder has become enmeshed with hookup culture, which refers to the broad quest for casual sexual relationships among young adults, particularly university students (Hess & Flores, 2016).

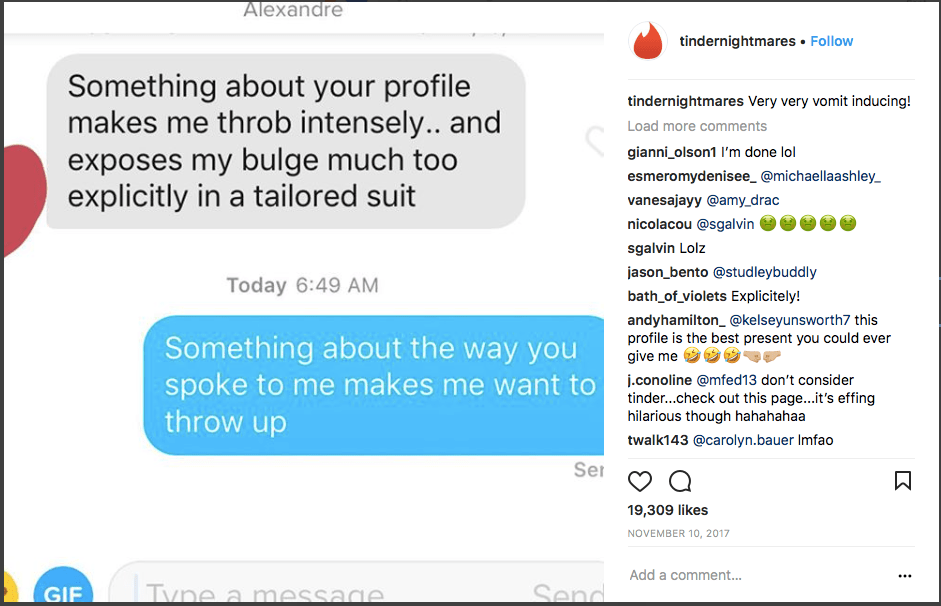

Because text messages between matches are maintained in a user’s app, it has become possible and popular to document (through taking a screenshot) and then re-contextualize these seemingly private conversations in other spaces online. One such context is Tinder Nightmares, an Instagram page that is dedicated to showing ineffective attempts by men to engage with women on the app. These Nightmares are typically overtly sexual, sometimes offensive, sentiments sent by men, and the responses from women tend to be funny and witty. In their analysis of the Tinder Nightmares Instagram page, Hess and Flores (2016) noted the counter-disciplinary function of this page, where these online dating interactions are made publicly visible and then called into question by the women who view these behaviors as undesirable. This type of action is what Jane (2016) called “feminist digilantism,” which is a strategy that has been crafted by women to combat sexism and misogyny online by “calling out” bad behavior. In the constructions of gender on the Tinder app, offline dating norms are adapted to the online space such that mediated interactions become a blend of existing scripts and online improvisation (Hess & Flores, 2016).

Figure 4: Example of counterdisciplinary response to toxic masculinity on Tinder. Screengrab from Tinder Nightmares Instagram page

Hess and Flores (2016) inferred that Tinder is seen as a competitive space, and thus men on the app may “feel pressure to engage in certain articulations of toxic masculinity that aid in establishing their power over women,” including sexually aggressive behaviors that aim to maintain women’s inferiority in online spaces (Hess & Flores, 2016, p. 4). These behaviors are then shamed on the Tinder Nightmares page, which further challenges dating discourses, as men are shown what is considered by women to be bad behavior that is based on existing traditions, while women are presented with scripts for addressing toxic masculinity in online intimate environments.

One such counter-disciplinary reaction to these lewd messages and toxic masculinity as a whole on the Instagram page is to call these individuals ‘creeps,’ ‘vulgar,’ ‘fuckboys,’ or ‘assholes’ (Hess & Flores, 2016, p. 8). Such labels and counter-discipline suggest updated norms for Tinder, thus showing how to successfully perform on the app (or not). In this way, women have been able to challenge toxic masculinity and affect new scripts for online dating (Hess & Flores, 2016). Because of the degree to which these scripts are circulated, Hess and Flores hypothesized that “for men who adhere to hypermasculine and heterosexist codes, it appears that the dream of successfully hooking up with women through these performances is over” (p. 15). Sadly, though, this sentiment seems to be a bit preliminarily hopeful. As described by Banet-Weiser (2015), just as popular feminism can have somewhat legitimately feminist results, the rise of popular misogyny can affect more organized opportunities to work against women’s social progress.

As Banet-Weiser and Miltner (2016) found, two such examples of this misogyny are men’s rights groups and the seduction community of pick-up artists (PUAs). Rachel O’Neill (2015a) conducted ethnographic research with the latter example, and she discovered that the men she studied were primarily concerned with improving their casual sex “game” (1.3) and, in doing so, treated casual sex as a commodity controlled by women. Banet-Weiser and Miltner (2016) attributed the anti-feminist sentiments of this community in part to unfulfilled entitlement of the belief that male success is inherently rewarded by beautiful women; PUAs are overwhelmingly younger white men who are not considered traditionally masculine and tend to be associated with the ‘geek/nerd’ label. As I show in the next section, despite the disciplinary function of the word ‘Fuckboy’ in Tinder Nightmares,the discourse of such toxic masculinity still suggests that Fuckboy masculinity is desirable, attractive, and inevitable.

Describe to me this “Fuckboy”

What do Fuckboys do?

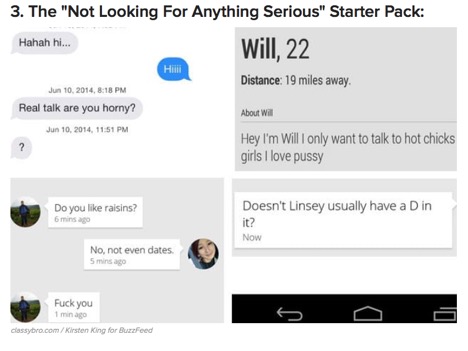

Fuckboy media often craft lists of identifying features and further categorizations of Fuckboy types (e.g., King & Ro, 2015; King & Parker, 2015; Complex, 2015; Holt, 2017); two such “types” can be seen in Figures 5 and 6. Throughout all of these many features, categories, and characterizations of the Fuckboy, no concrete formulation is evident. Indeed, Jacob Brogan’s article exemplified this contention: “Everyone knows what fuckboy means. And no one knows what fuckboy means.”

Briefly and generally, a Fuckboy is a young single man who uses social media to act duplicitously in pursuit of sexual relations with women. Typically, he deceives a woman by implying or outright stating that he has romantic feelings for her and/or would like to be in a monogamous situation with her when, in fact, he does not, and indeed he may likely be performing the same game with other women simultaneously.

Figure 5: An example of one ‘type’ of fuckboy. Note: Reprinted from 19 People who have reached peak fuckboy.

The specific conception of the name is somewhat unclear. Most articles that discuss the phrase’s origin point to hip-hop culture and the 2002 song “Boy Boy” by Cam’ron (2002). The timing of this song is potentially related to the first entry of the word “Fuckboy” on UrbanDictionary.com, the internet’s guide to slang, which first described the word in 2004 as “a person who is a weak ass pussy that ain’t bout shit [sic].” With 806 submissions on Urban Dictionary at the time of this writing, “Fuckboy” has become one of the most popular (and contested) slang words of recent years.

Killer Mike, another popular hip-hop artist who is linked to the christening of “Fuckboy,” has been quoted as saying, “You can identify Fuckboys…because they are always doing fuck shit. Just the dumbest, weirdest, lamest possible shit ever” (cited in Brogan). The original definition has evolved into further specificity, such that the Fuckboy is now regarded as “a (usually straight, white) dude embodying something akin to the ‘man whore’ label, mashed up with some ‘basic’ qualities and a light-to-heavy sprinkling of misogyny.”

Figure 6: Examples of fuckboys who use social media to seek casual relationships. Note: Reprinted from 12 Essential starter packs for fuckboys.

The Fuckboy’s general lameness may have developed into womanizing behavior because Fuckboys are “the worst kind of guy, or at least one who represents the worst trends of the present moment.” At the present, popular feminism has rendered mistreatment of women to be one of the worst trends of the moment, particularly because popular misogyny has risen concurrently. Another trend of the current moment is the increasing worldwide domination of social media usage. As noted by the retrosexual discourse, technological innovations are contentious, so the prevalence of computer-mediated communication may also be represented in the Fuckboy’s embodiment of current trends: all characterizations of this figure refer to his usage of social media platforms to pursue intimate or sexual relations with women. It is a key feature of the Fuckboy.

- Snapchat: This mobile platform’s affordances allow communication through text, photo, or video messages that disappear shortly after viewing, and the ephemeral nature of the app lends to its use being associated with ‘sexting’ (sending sexually explicit messages or photos) and secrecy. Fuckboys are said to often or exclusively communicate on Snapchat, which is linked to their use of the app to engage with many women at a time, despite an implicit monogamy with one (e.g., Dakota, 2015; Amaral, 2016; Jerry Studios, 2016; Moreau, 2017).

- Tinder: Tinder is a mobile dating app that allows nearby users to assess each other’s attractiveness based on a user-generated profile that can include photos and text. If two users are mutually attracted, they ‘match’ and are able to send direct text messages through the platform. Tinder is often associated with hookup culture and casual sexual encounters due to the geographical proximity of users. Fuckboys’ favorite app is purportedly Tinder, which is especially pertinent considering that Tinder allows each user to be in direct communication with many potential partners at the same time (e.g., Dakota, 2015; Sales, 2015; Amaral, 2016; Jerry Studios, 2016; Corley, n.d.). As mentioned above, displays of overtly sexual masculinity on Tinder are sometimes met with subsequent public shaming by women.

- Instagram: The most common Fuckboy applications of Instagram are posting shirtless selfies, indiscriminately liking or commenting on photos of attractive women, and utilizing the direct message function to privately communicate with attractive women (e.g., Dakota, 2015; Jerry Studios, 2016; SimpleSexyStupid, 2016; Holt, 2017).

Moreover, Fuckboys notoriously use direct message features, which include general person-to-person text messages or private messages on popular platforms; this is often called “sliding into DMs” (direct messages). Fuckboys apply this one-on-one affordance to send sexually based (often late-night) messages (see Figure 6) and arrange casual sexual encounters. “Netflix and chill,” which is understood as a euphemism for sex, is a go-to proposition for Fuckboys. Fuckboys frequently request nude photos from women through DMs, and they are also known to send unsolicited “dick pics” to women. A major complaint against fuckboys is their tendency to ‘ghost’ women by ignoring their direct messages and ceasing contact. Fuckboys ghost women as a way to discontinue relations, particularly after they have already engaged in sexual interactions.

Overall, the Fuckboy’s social media presence is scorned by female authors and used as a point of reference to demonstrate his duplicitous and immature behavior. The affordances of social networking sites, as described above, enable Fuckboy behaviors in ways that are not possible (or less) offline, and social media are the channel through which Fuckboys’ enact the familiar immature player masculinity, focused on sexual gratification and consumption of sex.

If fuckboys suck so much, why are they everywhere?

Fuckboys masquerade as nice guys, when instead they are more akin to a kind of “venomous creature” or a “contemptible faker.” Fuckboys are “the kind of promiscuous man who is manipulative and cocky while still being a worthless poser.”

He “will try to charm you with kind words, taking you out, telling you he’s different and acting really fun to be around,” said Gina Escandon, but, she warned, “Be speculative about the pretty face he puts on.” Fuckboys also “intend to inhabit a cultural identity that they may never achieve.”

These evaluations echo the tactic of the New Lad, who is said to have played the role of the New Man while out with women but returned to his ‘authentic’ self when back in an all-male environment (Gill, 2009b); the retrosexual has been accused of similar tactics (Anderson, 2008). Notably, despite the many anti-feminist statements in his article, Castillo claimed that a Fuckboy is not merely sexually promiscuous but is specifically a liar or trickster in this regard. Perhaps this suggests that the “real man” narrative of authentic masculinity as demonstrated by the New Lad and the retrosexual is no longer wholly believable or, indeed, that it was never truly convincing.

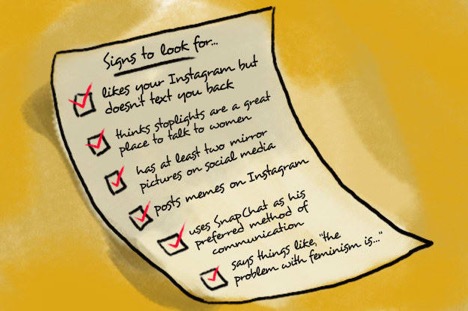

The significance of this deceit lies in popular media’s reaction to it: titles suggest that women should always be ready to unmask a Fuckboy. Online articles point women to ways to identify a Fuckboy, including such article titles as “15 Tragic signs you’re dating a Fuckboy,” “Here’s how to spot a f*ckboy in the wild,” or “How to tell if he’s a fuccboi”; another faction of Fuckboy media provides suggestions to women regarding what to do after they have identified Fuckboys, including how to learn to love Fuckboys, “foolproof reactions” to Fuckboys, and ideas of what to do instead of talking to a Fuckboy. This notion of exposure saturates the discourse. Rather than suggest the masculine cessation of this misbehavior, the discourse focuses on the feminine surveillance and management of it.

Figure 7: Social media characteristics of fuckboys. Note: Reprinted from 15 Types of fuckboys that need to fucking stop.

Additionally, many of the articles written by women utilize screenshots of text messages to reveal and deride Fuckboy behavior in the same way as the Tinder Nightmares page operates. This trend utilizes existing experiences and new clues to continuously update discourses of heterosexual dating culture in media. Images that are presented as real interactions with Fuckboys, like screenshots of direct messages, give female readers possible scripts for responding to alleged Fuckboys in their lives. The tips on how to deal with Fuckboys offer these readers guidelines for appropriate actions, and the whole of this media implies that women should be constantly vigilant in their suspicion and unveiling of Fuckboys. As one article noted, the Fuckboy discourse acts as a “way to call out the bad behavior that accompanies unchecked male privilege in the romance department.”

These scripts (see Figure 6) suggest that women should be responsible for the monitoring of heterosexual relationships. In this way, this discourse further insinuates that men are naturally to be sex-obsessed predators. It seems this uneven advice has not gone unnoticed by men in the world. In an article that defends Fuckboys, Johnny Dollar wrote that in terms of how a woman discusses a Fuckboy, “it’s as if she had no part in the non-relationship at all. It’s as if he just showed up and thrust this ‘what are we’ relationship onto her without her having any agency about it.” This passivity was addressed by a female author who claimed to have been treated poorly by many Fuckboys because she allowed them to have power over her actions. She felt that she became empowered herself when she began to engage in Fuckboy behaviors and craft her own sexuality by using unsuitable partners as sex companions:

“The biggest mistake I’ve made with these men in the past was to let their desires have priority over mine. I let them dictate to me what my feelings were, without questioning their Fuckboy logic. But if this past year has taught me anything, it’s that I no longer have a problem standing up for myself. It’s possible, empowering even, for a woman to engage in Fuckboy-esque behavior as a method of genuinely expressing what she wants.”

The final portion of this quotation is also in line with Gill’s (2009a) finding in the sex advice of women’s magazines and postfeminist media culture in general (Gill, 2007a), which encourage women to learn and embody a depth of sexuality that is akin to a pornographic standard. It is particularly excusable because Fuckboys primarily desire sex, so when women identify Fuckboys, they can make their own individual choice to either conform to Fuckboys’ desires or cease contact with them.

Despite that Fuckboys “treat women as if they are sex toys come alive” (McGrath, 2016), women are “still addicted to them” (Peterson, 2015). As Castillo asked, “Why does she keep falling in love with Fuckboys despite the fact that she claims the opposite?” Keeping in mind Gill’s (2009a) discovery that women’s sex advice advocated dating men who are known to be unsuitable as partners as a means of improving the self and further crafting a sexual subjectivity, then it is clear why Fuckboys have not been eradicated from contemporary mediated dating life (see Figure 8).

One female columnist reconciled her decision to intentionally engage with identified Fuckboys: “But what am I going to do, not date at all? Sincerely sit around and wait for the right guy to come along? Fuck that. I’m too impatient and too horny to wait, and too broke to not accept free drinks.” This echoes the discovery by Gill (2009a) that women are encouraged to put work into their dating life, and their work will eventually be rewarded by a committed relationship with an ideal man; in the meantime, they should continue to hone their sexual knowledge, present themselves as sexual subjects, and practice their relationship expertise with unsuitable men.

Figure 8: Screen grab example of a woman purposefully engaging with a fuckboy. Note: Reprinted from Jerry Studios’ FUCCBOI (Official music video).

Where’s the disconnect?

Shaun Brown wrote a piece in which he expressed worry that he would remain a Fuckboy forever, despite wanting to dismiss his “childish ways” and the “Fuckboy ways that have come to define our twenties for so many of us [men].” He further said that he hopes someday to “grow up” and let go of the “man-child” he feels that he is as “a Fuckboy at 29 years old.” He explained the cause of Fuckboy behavior as a result of emotional “wounds,” which fits Hansen-Miller and Gill’s (2011) narrative of the player in lad flicks having been emotionally stunted by a past trauma. When considering this affective emotional turmoil in combination with how Fuckboys are described almost entirely through social media use, it is clear that this figure does not naturally occur in all men.

Trends from lad flicks suggested that a successful woman who puts in work can affect the change that will craft an immature man into a suitable partner (Hansen-Miller & Gill, 2011). The combination of these discourses suggests that men who act like Fuckboys are just waiting for the right woman to tame them into a successful man. In this way, media imply that Fuckboys can continue their immaturity and use of women for sex, and women should continue to engage with Fuckboys to practice heterosexual skills until one Fuckboy eventually matures into an appropriate partner.

In the Tinder Nightmares context of women replying to Fuckboys with witty remarks (Hess & Flores, 2016), April Lavalle wrote a satirical piece regarding the evolution of a Fuckboy to a “fuckman.” In her evaluation, Lavalle contended that a fuckman is more mature than a Fuckboy, but still engages in many of the same behaviors. The fuckman seems to be an intermediary between the Fuckboy and the mature monogamous husband type of man, almost exclusively because he acquired “a really good job in finance.” Interestingly, fuckman is still rife with undesirable qualities, most of which are expressed through social media usage, and the slightly evolved aspects of the fuckman are rather unrelated. For example, an indication of his maturity is that he “traded his muscle shirts for J. Crew button-downs,” though he still sends unsolicited dick pics and asks women for nude photos twice per week.

In terms of Fuckboys’ purported inevitability, the title of one article even broadly claims that all “dudes” are Fuckboys until they reach a certain part of their lives in which they mature: “somewhere in their late twenties or early thirties, a dramatic change takes place. They hang up their f-boy pants and put on their adult, father/husband pants…all men are Fuckboys until they decide they aren’t anymore.” It is interesting that the author suggested aspects of both nature and choice regarding the existence of Fuckboys. This quotation’s premise that all men are Fuckboys assumes a naturally inherent feature of (heterosexual) men that prompts them to trick women into sex, but their Fuckboyhood ceases of their own volition, when it behooves them to stop.

This revelation is especially potent when considered in combination with the inevitable and natural “boys will be boys” characterization, but it also perpetuates the stereotypes in past sex advice that men and women inherently want different outcomes from intimate relations: women are always looking for the right partner but will settle for sex, while men are always looking for sex but will settle for the right partner. A natural gender divide is implicated in this difference, but the stereotypes cannot possibly apply to everyone. Regardless, Dollar contented that disdain for Fuckboys stems from women who “caught feelings and then couldn’t make a Fuckboy their boyfriend.”

Castillo also used natural explanations of Fuckboy behaviors: Fuckboys assert their “rightful dominance” in society and getting what they “deserve” (i.e., sex). He declared that “women want men who are men” and “real men do whatever they want,” while women “use their vaginas as leverage and implicitly (or explicitly) threaten to withhold [sex] if men don’t acquiesce to their demands.” Castillo’s reframing of women’s grievances with Fuckboy behavior into a narrative of desire and his neglect of women’s agency and consent could have many dangerous implications when considering thatthe seduction community and PUAs have recently been linked to several sexual assaults and rapes. In the same way as Fuckboy media offer scripts for appropriate female behaviors, the male defenses of the Fuckboy can act in a similar manner; what may be taken as a joke by some people may be interpreted as instructions to another.

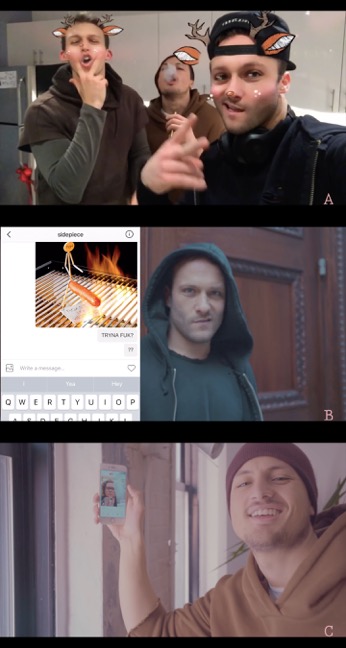

Figure 9: Fuckboys’ use of social media. A) Snapchat filters; B) SMS and MMS; C) Indiscriminately swiping right on Tinder. Note: Reprinted from Jerry Studios’ FUCCBOI (Official music video).

Conclusion

The Fuckboy represents a masculinity which has developed in conjunction with, and perhaps because of, digital and social media. The general characteristics of this figure draw upon previous depictions of masculinity in postfeminist media culture and re-contextualize these ideas through trends of the current moment, including social media and popular feminism. The Fuckboy may represent some of the first widespread recognition of this player masculinity as inauthentic, particularly through his social media self-presentation, though this figure is also addressed as if it is an inevitable and natural aspect of heterosexual dating life. The Fuckboy represents a childishness that is reflective of the player in lad flicks of the early 2000s, and media show that this type of masculinity matures to become a monogamous family man only when the work of a successful female partner prompts an overhauling lifestyle change.

These characterizations of women in contemporary heterosexual dating life recommend crafting a sexual subjectivity and assert that women need to be constantly attentive to what men think, feel, and want. Women are meant to manage and surveil these relationships, and the Fuckboy discourse suggests that women must identify Fuckboys, perhaps still engage with them to craft their sexuality, and invest work into their relationships until a Fuckboy decides to mature into a real man who is ready for monogamy and a family.

The female labelling and spreading of the word “Fuckboy” has given women a foundation to determine this behavior and vilify it. On the other hand, it also maintains aspects of postfeminism in that it affords agency to the women, not to the men, suggesting that this is “just the way it is” and that women should be vigilant in finding and calling out this behavior, but men are not encouraged to change their ways. As the Tinder Nightmares article points out, though, this may be a means for women to change the narrative of dating norms by discouraging negative behavior.

However, despite the above characterizations of the Fuckboy as a specific type of man who, on some level, truly has no respect for women, I posit that the purported inevitability of this character is due to the applicability of these tendencies to a great many single men. Fuckboyish behavior is representative of several trends of the contemporary single man: the Fuckboy is everywhere because the Fuckboy is every man.

In Western culture, it would be truly a feat to find a man (or woman, to be frank) who has not at some point ignored a text from a woman he had been intimate with, or one who told a woman something she wanted to hear when it was not entirely truthful or found that he did not have as strong feelings for her as he originally thought. These seem to be ‘normal’ behaviors of the time, but to extend just beyond the Fuckboy discourse’s embroilment of tensions, there are clues to the intentions: Rather than a manipulative and dishonest predator of a man to fit with the gullible and passive femininity, women are actively voicing and mediating their romantisexual displeasure with the lack of respect and communication from men, who may indeed just be confused and unaware of the gendered power structures that still advantage them.

While sex is, at this point, an inevitable part of contemporary Western dating life, Fuckboys may not have to be.