Who are the Instagram Husbands?

“Behind every cute girl on Instagram is a guy like me…and a brick wall” (The Mystery Hour, 2015), explained the opening of the viral YouTube “Instagram Husband” video in an interpretation of the saying, “Behind every great man is a great woman.” The subversion of this mid-20th century infamous feminist rally cry operates within the internet’s notorious re-contextualization of culture in a postfeminist acknowledgement and renouncement of feminism; the irony in the video, which highlights a recent trend of men who feel pressured into taking photos of their female significant others (who are typically bloggers) for Instagram, ensures that its representations of gender are firmly entrenched in the tenets of postfeminist media culture.

Online virality, or “going viral” – when a creation (e.g., blog post, video, meme) gains widespread short-term popularity – has drastically affected how online media are produced and consumed. For The Mystery Hour, a sketch comedy group from Missouri, USA, their 15 minutes of viral fame came from their short Instagram Husband (2015) clip. At the time of this writing, the video had been viewed on YouTube approximately 6.6 million times and mentioned in dozens of news sources, most of which have praised the video for its comedy and realistic depictions of a seemingly new phenomenon in the social media realm. The phrase itself has since become embedded in common online vocabulary, with the significant others of successful bloggers, social media influencers, traditional celebrities, and political figures now touting the “Instagram Husband” label.

The video reveals a statement on social media use, with the so-called ‘husbands’ placed in the role of unwitting photographer, or “human selfie stick,” and the women cast as controlling and Instagram-obsessed self-made models who demand documentation of their everyday mundanity. The men speak of their plight to the camera in a confessional style; the women are not given this voice. Throughout the video and its accompanying website, it is clear that the women are concerned with developing their social media profiles in pursuit of some level of notoriety, explained in the video as narcissism and vanity.

Though the creators of the video reportedly had no intention of discussing contemporary gender politics, such a commentary is inherent in the plot’s husband/wife divide; its critique of (particularly) women’s social media usage is especially clear from the words of Jeff Houghton, the film’s creator and starring actor, who has asserted in an interview that the plot “felt universal” to the internet’s culture. The analysis of this case thus provides a unique opportunity to reveal the interplay of current understandings of gender and social media use in broader society.

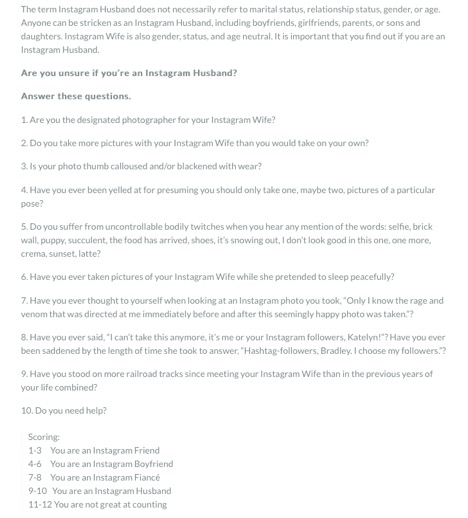

Figure 10: Instagram Husband symptom checker. Note: Reprinted from Instagram Husband Tumblr.

Despite Houghton’s claim of knowing “plenty of Instagram husbands that are the women behind the camera” and that “[the actor] Nate from the video is the one more obsessed with Instagram than Sarah, his girlfriend” in real life (as cited in Griner), the status of gender in media resulted in Houghton’s belief that depicting real Instagram usage (i.e., an even divide of 50.6% female and 49.4% male users) “might be confusing” (as cited in Griner). By maintaining the gender stereotype of women’s social media vanity in the video, Houghton and The Mystery Hour team have aided in perpetuating heterosexist notions of work, connectivity, and natural sexual differences within the emerging context of social networking sites.

It is widely accepted that the Instagram Husband video coined the corresponding term and was the vehicle of this figure’s naissance, and thus each subsequent mention of the term implicitly or explicitly references it. The progression of the phrase in subsequent articles and online sources is carefully considered in this chapter’s analysis to represent the evolution of the Instagram Husband discourse.

To identify an Instagram Husband, InstagramHusband.com offers a list of symptoms (see Figure 10) that range from “Do you take more pictures with your Instagram Wife than you would on your own” to “Do you suffer from uncontrollable bodily twitches when you hear any mention of [Instagram-related] words?” Beyond the benign-to-oppressive symptoms, Gander’s (2016) interview with the video’s creator, Jeff Houghton, has supplied a more precise definition: “An Instagram husband refers to anybody who has to begrudgingly take pictures of their significant other” [emphasis added]. The impact of this quote is its qualification of these men being forced to ‘begrudgingly’ help their significant others.

This definition assumes an element of force on the wives and disinterest on the husbands, which implies a power relationship in which men are the “victims,” “poor souls,” or “unsung heroes” of social media Cave, 2016). Of course it is ironic, so of course it is a joke, but the domestic violence they simulate to evoke their victimization is not a joke, nor is the history of women’s oppression and harassment in the workforce. The supposed universality of this figure directly correlates it to the offline world and, combined with its success, imprints new influences on perceptions of gender. But, most importantly, why are these men so unhappy to help their partners?

History

The power of Instagram

Instagram is a photo- and video-based social media app intended for smartphone use that was launched in 2010 and has blossomed into one of the most widely used platforms across the web. Marwick (2015) has considered Instagram to represent the intersection of several current trends: the influx of real-time user-generated content, a heightened presence of the practices of celebrity and microcelebrity culture, and a vehicle for conspicuous consumption.

In particular, Instagram encourages a dynamic more akin to fandom and admirable observation than friend-like interaction (Marwick, 2015). This dynamic occurs because users have the option of having a ‘public’ or ‘private’ profile; with a public profile, anyone may ‘follow’ a user in a unidirectional manner and view all of their shared content; it is not necessarily expected that the user will ‘follow back.’

Such a dynamic forges several trends, especially “Instafame,” a portmanteau that represents fame garnered from having a significant number of followers on Instagram. While the top-most followed accounts currently boast around 100-200 million followers, Instafame is relative to the individual user, so achieving only hundreds or thousands of followers can be a mark of pride for some (Marwick, 2015). Instafame can arise as native to Instagram, meaning a user’s loyal and attentive following has been garnered solely from this app, but many Instafamous users utilize Instagram as complementary to another primary pursuit, such as a blog, small business, or aspiring music career.

Instafame is a type of microcelebrity, which represents a juncture between traditional celebrity and the average person, as it requires “reproduce[ing] conventional status hierarchies of luxury, celebrity, and popularity that depend on the ability to emulate the visual iconography of mainstream celebrity culture” (Marwick, 2015, p. 139). Today, this ethic generally necessitates adopting the practices of successful people who display an ‘authentic’ persona as the outcome of work to create a consistent online presence.

Microcelebrity, Instafame in particular, thus requires successful targeted and deliberate self-branding, the techniques of which have been appropriated from consumer branding practices and applied by individuals in accordance with neoliberal values of individualism and entrepreneurialism. Furthermore, this self-branding represents self-commodification, for which online photographs are an increasingly popular and profitable channel. In the social media era, celebrity has evolved from an almost entirely unattainable role into “a continuum of practices that can be performed by anyone with a mobile screen, tablet, or laptop” (Marwick, 2015, p. 140).

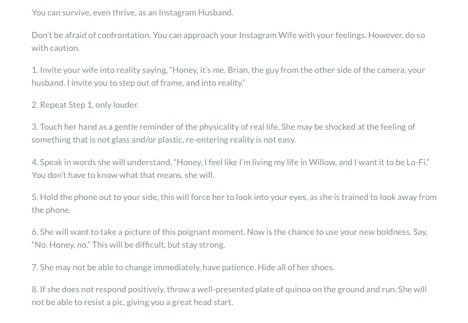

Figure 11: Tips for Instagram Husbands to approach their wives. Note: Reprinted from Instagram Husband Tumblr.

Make me Instafamous?

The luxury status of traditional celebrity activities and the photos celebrities post online ensure that average users can only emulate these practices with the assistance of an additional person to play the part of (micro)celebrity photographer; as the layperson attempts to rival celebrity practices, the Instagram Husbands are those who have been asked to assist in this production. This trend of disseminating content that directly mimics and refers to celebrity culture has been deemed “aspirational production” by Marwick (2015, n.p.):

While nobody may actually be paying attention, aspirational producers want the audience to think that they are being snapped by the paparazzi even if their pictures are actually taken by a best friend or boyfriend…by positioning themselves as worthy of the attention given to celebrities, and by using the visual tropes of celebrities, [aspirational producers] position themselves.

Interestingly, simply by engaging in aspirational production, users may indeed advance their Instafame. Many popular social networking platforms) are predicated on algorithmic content dissemination, and Instagram’s algorithm rewards patterns of photographic content that has already attracted attention(Carah & Shaul, 2016). In this way, while algorithms are not created to purposefully perpetuate traditional ideals of, for instance, beauty or gender, they do favor what has already been determined to draw popularity, which fits into these conventional scripts (Carah & Shaul, 2016). Algorithms can significantly impact which people and how many people view a post: the key to developing celebrity (or not).

Instafame and microcelebrity are considered derivatives of the attention economy of recent decades, in which merely building numbers of views or clicks online equates to profitability in terms of rising social currency and social reinforcement. And an attentive audience may produce more than just status, as explained within the notion of the demotic turn, which is the trend of ‘average’ people achieving mainstream fame, brief or otherwise through social media notoriety (Marwick, 2015; Khamis, Ang, & Welling, 2016).

One development from the demotic turn is social media influencers, who begin as ‘ordinary’ social networking site users but amass a following through publicizing their personal lives; these people become professional influencers through “monetize[ing] their following by integrating ‘advertorials’ into their blogs or social media posts and making physical paid-guest appearances at events” (Abidin, 2016, p. 3). This understanding has been further exacerbated by growing partnerships between big businesses and influencers. In this way, “microcelebrity points to the growing agency, enterprise, and business acumen of everyday media users” (Khamis, Ang, & Welling, 2016, p. 7). The use of self-images is extremely important. Posting portraits of oneself in high quality – in both composition and editing – is imperative to the success of an influencer and building a profitable fan base both online and off (Abidin, 2016); assisting with these photos is the Instagram Husband’s role.

The male gaze

To mimic the beauty ideals of celebrity culture and amass likes and followers, one must present oneself as physically attractive. The curation of this content and the consistency required from self-branding relies on strategic planning and self-surveillance; a social media following is predicated on vanity, narcissism, and self-objectification. For women, this mirrors Gill’s (2007a) concept of the female internalization of the objectifying male gaze (see Chapter 2) in which former structures of gendered discipline have been altered.

Originally theorized in filmography by Laura Mulvey (1999), the notion of the male gaze is the articulation of female objectification in visual media. In this relationship, the male fantasy is imposed onto a female character in an inherent dynamic of an active and passive participant. Mulvey has said, “In their traditional exhibitionist role, women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness” (1999, p. 837).

Figure 12: Screengrabs of Instagram Husbands in action. Note: Reprinted from the Instagram Husband viral video.

In terms of visual media, the audience was historically given the masculine role of looking at the female character’s looked-at-ness through the lens of male eroticism. Gill (2007a) has postulated that in postfeminist media culture, the objectifying male gaze is removed from the masculine position and, instead, constitutes women’s subjective and self-disciplining self-constructions: “sexual objectification can be (re-)presented not as something done to women by some men, but as the freely chosen wish of active, confident, assertive female subjects” (p. 153). This shift characterizes a change in social power, such that power upon women’s likenesses no longer stem from the masculine looking but arise from within the feminine interpretation of the self.

A woman presenting herself as such an object insinuates “an agented subjectivity that threatens the male-dominated social hierarchy” (Marwick, 2013b, p. 17), and there is evidence that societal masculinity has felt discomfort with the rising of feminine power over the feminine self. Male backlash against this power transformation can manifest in several ways. For one, men may be rejecting media platforms altogether: Laura Portwood-Stacer (2012) has discovered that the masculine positioning of independence recommends avoiding technological connectivity, particularly on social networking sites; this advice is reflected in the early 2000s’ retrosexual figure. More commonly, reactions against feminine power and feminism are often expressed through and alongside the use of irony so as to be presented publicly but under the guise of a joke. As Gill (2007a) has explained, by ironically utilizing retro sentiments and alluding to the misogyny of years bygone, “sexism is safely sealed in the past while constructing scenarios that would garner criticism if they were represented as contemporary” (p. 160).

Why does it suck to be an Instagram Husband?

The view from the other side

A lack of autonomy is a common complaint among Instagram Husbands. The Instagram Wife acts as creative director: she chooses the setting, wardrobe, angles, poses, and purposes of the photos of her, and then she edits and posts them to her own Instagram account, which effectively gives creative attribution to herself. In doing so, she renders the Instagram Husband somewhat absent in the processes of conception and dissemination, and his involvement in the creation is explicitly physical: a finger to push a shutter button.

Buxton has described video creator Jeff Houghton’s similar Instagram Husband qualms: “His only current complaint is that his wife tends to look off into the distance and adopt a dramatic pose rather than smiling in photos.” Here, Houghton has renounced the agency that his wife assumes in crafting her social media persona because it does not reflect his fantasy of her as an object (see similar in Figure 14); he wants her to smile.

One real-life Instagram Husband has said that he is “fortunate” for being permitted to take candid shots of events or activities that actually happen rather than snapping photoshoots staged by his wife: “I would have a hard time swallowing it, I think, if it were something that didn’t feel like it looked in real life” (as cited in Buxton). The important distinction between a staged and a candid photo is that, in the case of the latter, the Instagram Husband acts relatively freely in the creative direction of the photo-taking activity and produces a result that is crafted by his eye – in other words, a candid photo is the reinstatement of the male gaze to the man.

Confirming this discontent with photographing feigned authenticity, another Instagram Husband has disliked how his wife “acts natural” in the photoshoots (as cited in Clark), rather than allowing him to photograph her authentically being natural. By expressing displeasure with aiding in his female counterpart’s self-branding, rather than having role of the creative director himself, the disgruntled Instagram Husband expresses a longing for the traditional gender power dynamic in which objectification of the female body in media occurred strictly from man onto woman and into mass consumption.

In Susan Sontag’s iconic essays, On Photography (1977), the author asserted, “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed”(p. 4). She has further compared photographing to violating, as it is based on the photographer creating an object of the person photographed and “seeing them as they never see themselves” (p. 14). As I have similarly discussed elsewhere, Sontag’s theory is helpfully applied to this figure: by shooting photos, the ‘human selfie stick’ takes on the physical role of appropriator and violator, but not the creative role. He is instructed to see his wife as she wants herself to be seen, so he is under the explicit guidance and vision of the one being photographed, appropriated, and violated. The Instagram Husband is a man who creates an object (in the form of a digital photo file) of a woman in a process in which he has not been given implicit or explicit permission to appropriate her; in other words, each time an Instagram Husband takes a photo is the microcosmic instantaneous manifestation of the societal male gaze being taken from the man. He still has the literal sight (though it is sometimes not even necessary – see Figure 12, bottom), but the fantasy enacted is not his own. Instead of holding the power of the male gaze, the Instagram Husband himself is made into an object: a selfie stick.

Figure 13: Screengrab of Instagram Wife chiding Instagram Husband for drinking a sip of coffee before she captured a photo. Note: Reprinted from the Instagram Husband viral video.

Fragile Husbands

The video’s confessional style highlights the plot’s irony to enhance the gendered claims while ensuring the video remains strictly within the category of comedy. Meanwhile, the confessionals provide the viewer with Gill’s (2007a) “knowingness,” which serves to praise the viewer for their ability to understand the ‘real message’ within the media; in this case, by giving the men a voice to speak directly to the audience while denying the opportunity to the women, the viewer understands the point: women are silly for taking social media seriously and wasting their men’s time. The greatest irony of all, however, was that the Instagram Husbands have proposed to help their brethren on their website using methods that all stand on social networking sites and, more so, that these men became famous haters of social media through social media viral fame. The prototypical postfeminist pot calling the kettle black.

The InstagramHusband.com site’s suggested ways for Instagram Husbands to approach their wives (see Figure 11) and receive help are a flash to the past, postfeministically: ‘Medicine’ is suggested to relieve the symptoms of being an Instagram Husband, and the medicine of choice is to visit the website for Jack Daniels Tennessee Whiskey – a notably masculine-associated drink and a nod to the good ole days of when men were simply men, not Instagram Husbands. The Instagram Husbands have also given advice for their comrades to connect with spirituality to cope with their role of photographer, including a direct link to a YouTube video entitled, “What happens if you shoot an iPhone 6?”; the mobile device is blasted with a gun.

These aggressive suggestions for surviving the simple act of taking photos are remarkably retrosexual in nature through their rejection of all notions of femininity and technology, as what retrosexuals love most is their “not-inconsiderable fear of modern technology.” Moreover, the retrosexual requirement to act in a chivalrous – yet disinterested – manner toward women coincides with the Instagram Husband’s role, which has been equated to “basically the modern day form of chivalry.” Interestingly, the old form of chivalry, often equated to holding a door for a woman, seemingly bore little effect on a woman’s career.

Instagram Husbands’ displeasure with taking photos for Instagram may also stem from Instagram being ‘snapshot’ photography, and this type of domestic or family photography has long been viewed as a women’s job. Accordingly, one real-life Instagram Husband has likened his role to “the new version of a man having to hold a woman’s purse” and suggested that he feels “embarrassed” when taking shots of his wife in public. Another husband has suggested that being an Instagram Husband is emasculating because he must carry a camera slung over his shoulder, a handbag, and an iPhone – items associated with femininity and connectivity.

Banet-Weiser and Miltner (2016) have defined this repulsion as “a (heterosexual) masculinity that is threatened by anything associated with femininity (whether that is pink yogurt or emotions)” (p. 171); in other words, it expresses “fragile masculinity.” This male distaste is a rising trend in increasingly many areas on the web. The authors have suggested that the influx of expressions of emasculated manhood online may have been triggered by the economic crisis in 2007-2008; the crisis left many men struggling financially and perhaps hesitant to accept and support new types of stereotypically feminine work that arose around that time, particularly those predicated on online female self-representation (and thus self-objectification) such as bloggers. Disavowal of feminine qualities in masculine roles is certainly not a novel idea (see New Lad and Retrosexual, Chapter 2), nor are the hypermasculinity and irony that are typically employed to scorn femininity in response to fragile masculinity. The novelty of the Instagram Husband discourse is that it is the latest manifestation of this fragile manhood, and the first time fragile masculinity is directly associated with the emergence of women having social media careers.

Figure 14: A seemingly imagined dialog of an Instagram Husband attempting to input his own creative direction. Note: Reprinted from Instagram Husband Instagram Account.

With these retrosexual tendencies, despite the creators’ assertation that this figure is inclusive and non-gendered, the Instagram Husband discourse becomes accessible only to heterosexual men who feel their masculinity is threatened by participating in an activity that has been deemed too feminine and gives women power over their own objectification.

However, real-life Instagram Husbands have revealed that their experiences have not been as horrible as they let on, and indeed they may have learned about photography and social media a new realm of culture (Buxton, 2016; Clark, 2017). One man said, “After a lot of practice, I feel like I can speak her language now.” While this comment exacerbates notions of natural sexual differences, it also demonstrates that if or when the feelings of emasculation subside, it may be possible to open up a new form of acceptable masculinity and perhaps even find a common interest with a woman.

The continued Instagram Husband discourse

The Instagram Husband has been re-contextualized in mainstream media since the video’s release. As Michelle Houghton, wife of the video’s creator, stated, “Now, if you say, ‘Can you be my Instagram Husband?’ someone will immediately understand what you’re asking them to do.” Popular media have suggested that musician and producer Jay Z, actor Ryan Reynolds, director Judd Apatow (famed for ‘lad flicks’), and even former President Barack Obama have held the Instagram Husband role, even if there is evidence of only one photograph being taken (Baila, 2017; Feldman, 2017; Harris, 2016; Sisavat, 2017).

After the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual event (known as the “Met Gala”), a high-profile evening for elite celebrities, an article emerged that showed “The best Instagram Husbands of the Met Gala,” all of whom were somewhat famous men taking photos of their similarly famous wives or girlfriends. Through these newer interpretations of the figure, it is now implied that any man who is seen taking any photo of his wife, as long as either of them are remotely famous, is thus an Instagram Husband; there have even been further subversions of this dynamic that do not require the presence of a woman (see Figure 12). This definition then celebrates the efforts of men in a mundane task, snapshot photography, for which women have been responsible since the dawn of the medium.

Finally, after the success of the video, the Instagram Husband has evolved into a paid position. TaskRabbit, an online platform that facilitates small-scale errands and activities, developed a limited-time offer to rent an ‘Instagram Husband’ for New York Fashion Week. This offer was aimed at fashion bloggers, and the service was so popular that it was reiterated for the London version of the same event. The price tag for such an arrangement was around USD$45 per hour, and the notion that the gendered aspect of a video inspired a real-life luxury service will surely have great effects on the Instagram Husband and social media discourses in the future.

Figure 15: Shared headline and image of a news article referencing the Instagram Husband. Note: Reprinted from Instagram Husband Instagram Account.

Conclusion

This chapter has presented the Instagram Husband as it was conceptualized by the eponymous video created by the comedy group The Mystery Hour (2015) and subsequent mediated references that have acted to shape the definition of the figure in popular culture. I have shown how this figure demonstrates the new manifestations of gender that have infiltrated societal consciousness through social media. This masculinity figure grew from the shaping of the photo-sharing social-networking app Instagram into a platform for self-branding, microcelebrity, and conspicuous consumption.

On Instagram, conventional images of traditional celebrity are frequently emulated by users to increase their metrics; for those who can garner enough Instafame to gain recognition by advertisers, microcelebrity can turn into an economically profitable career. For those who may not want to follow this path, their presence and activity on the app can still result in increased cultural capital, self-actualization, and participation in the online economy. As the so-called ‘Instagram Wives’ act as aspirational producers, they become essential players in the brand economy that is steadily increasing throughout social media.

The Instagram Husband concept operates on a basic level as a reaction against the mirroring of traditional celebrity, but its reliance on gender stereotypes makes a greater statement. While Houghton has claimed in interviews (Griner, 2015; Buxton, 2016) and on the official Instagram Husband website that being an Instagram Husband is not gender-bound to men, the reality is that discourses do not exist in a vacuum. Gender backgrounds, including women’s emergence in the workforce, their historical responsibility for snapshot photography, and their internalization of the objectifying gaze, mean that the seemingly intuitive choice was to form the ‘human selfie stick’ as a masculine figure; the pull to produce media that is entertaining but “still hews to conventionally sexist tropes” (Marwick, 2013b, p. 12) was overwhelming. Despite real-life evidence to the contrary, (postfeminist) media stereotypes of gender – particularly the masculine antagonism toward feminism and rising female power – rendered the distinction between the two roles as ‘naturally’ male/female in an environment in which every action of women is surveilled and critiqued while men seek applause for engaging in the simplest of domestic tasks.. The creators missed an opportunity to make an accurate and useful statement on social media’s part in the changing of photography dynamics.

Through postfeminist media culture’s attention on self-surveillance and constant work on the body and the self, particularly for women, the recently female-internalized male gaze has left masculinity’s role in visual media in question. The Instagram Husband figure is a male response to this uncertainty; it is masculine backlash to the shifting power of visual media’s objectifying gaze to the feminine, and the video’s sentiments express a desire for the reinstatement of traditional gender demarcations. With the video’s suggestion that women’s social media practices in pursuit of capital is a hindrance to the men in their lives, these men aim to regain power by insisting that their time should have precedence over their wives’ careers. As Moore has written, the Instagram Husband video – “an accidental ode to the still-shitty gender dynamics of success” – relies on humor contained within the novelty of men playing a supporting role in their wives’ careers.

The video’s humor is in its use of irony, which allows for deeper contradictions of gender representations in overall media culture and adds to the ambiguity of how gender is articulated, particularly in this online format. A simple comedy becomes a channel for normalizing problematic gendered concerns: 1) derision of women taking social media use seriously for cultural or economic capital gain, 2) male complaints against female career success, and 3) a retro sense in which men aim to readopt the power of the female-objectifying male gaze. Joke or not, media affect other media, and media influence societal perceptions; I could have taken this video as a laugh and moved on with my day instead writing half of a thesis on it, but, as Gill has said, in a time when “being passionate about anything or appearing to care too much seems to be ‘uncool’” (2007a, p. 159), I choose passion.